Interested in restoring your photos?

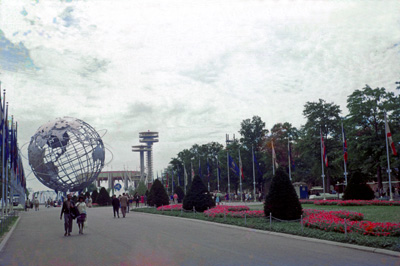

If you were lucky years ago, you not only went to a World's Fair, but you also took pictures of the big day. Or perhaps you have inherited a box of old pictures from your parents, or found them at a yard sale. Hoping to relive the fun of days past, you fire up the trusty slide projector, ready for a trip back in time. All too often, the big moment is ruined when the slides hit the screen. The colors seem odd, and there's dust and scratches everywhere. Even worse, some of the slides have become moldy from too many years of storage in a damp area. Decades of wear and tear, combined with the shifting of the color dyes, have turned those once vibrant images into something far less than what you had expected.

In the days before computers, you would generally have been out of luck. Restoring these photos would have been a timely and costly proposition, assuming that the work could even have been done in the first place. Happily the tools are with us to breathe new life into these faded treasures of days past. With a little effort, some patience and yes, some money, minor miracles can be performed.

All too often people have told me they tossed out the negatives to their photos (my mom did that for almost all of ours, saying she could never see the need for copies and wanted to reclaim the space) and now all they have left are faded or wrinkled prints. Well, it may not be too late - if you're the patient type, or pay someone to do it for you.

Here's an example to whet your appetite:

This slide from the 1964-1965 New York World's Fair has obviously seen better days. The colors have shifted badly and almost faded away. Much of the surface has been attacked by mold or mildew, leaving large blotches of strange colors. To make things worse, the slide was over-exposed when originally shot, and now is dusty and scratched. |

|

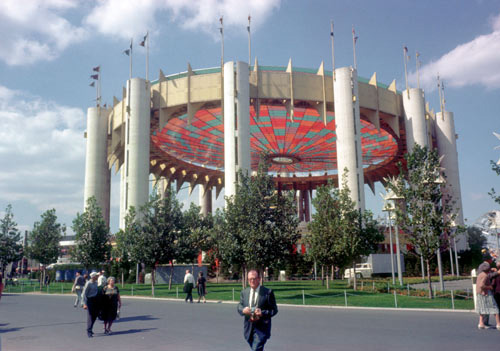

Thanks to the Nikon Coolscan V scanner and Photoshop the wonders of Flushing Meadows can be brought back to life. The colors are back, and the mold, dust and scratches are gone. As a bonus, the badly overexposed sky has also been corrected, revealing the clouds for the first time. |

|

I have received numerous letters and e-mails asking how I have fixed the photos on the site and the CDs. I don't consider myself an expert in the field, but am happy enough with my results that I wanted to encourage others who have their own photos rotting away to take the time to bring them back to life. I put this page together back in 2009 to help show what can be done to old slides, negatives, and photos hoping that it might encourage others to safely preserve their family history. Some of the technology has changed a bit since then, but the basic principles are the same.

So, without further introduction, some suggestions.

1) The scanner is the key

Before you can do any editing on the computer, you'll first have to get the original slide, negative or print scanned into a digital format. I use several different tools for this step based on the source media. For 35mm slides and negatives I thoroughly recommend the Nikon Coolscan V or Coolscan 5000 scanners. These are the best pieces of electronic gear I have ever purchased. What makes them so special? Well, besides being able to scan at a respectable 4000 DPI resolution, the Coolscan is able to remove most surface defects and to restore color automatically. It does this through a Kodak technology called Digital ICE. This magic is done by shining an infrared beam through the film and calculating the thickness of it. Thinner spots are considered to be scratches and thicker spots are dirt. The scanner then does a fabulous job of mathematically removing those defects from the final digital image. It works far better than you could possibly believe. Without it you will be spending WAY too much time manually removing this type of damage.

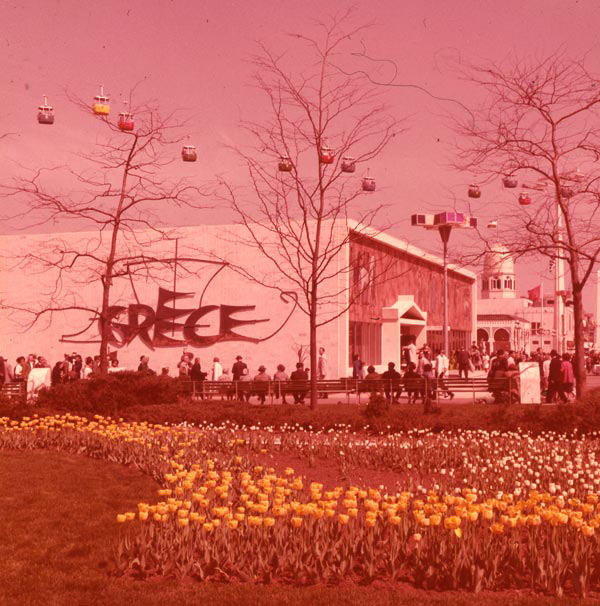

Besides fixing the surface defects the scanner can restore most color to faded images. A general rule of thumb is that Ektachrome images will have shifted towards the blue end of the spectrum, with Kodachrome turning red. Some pictures, especially those on non-Kodak stock or commercial souvenir slides, will have turned so red that you would swear they were beyond salvage. Happily a good scanner can prove you wrong.

Here's a souvenir slide sold at the 1964 Fair. Like most commercial slides of the time, the colors have faded away, and there is visible surface dirt and scratches. This scan was done without any of the correction features in the scanner turned on. |

|

A pass through the scanner with correction turned on has things looking much better. The color has started to come back, and most of the surface defects are gone. Processing time so far? About 4 minutes. |

|

Playing with the colors in Photoshop really turns things around, getting the correct colors back for the pavement, sky, skin tone, etc. And just to make it more interesting, a few clouds were added. Total time to restore the slide? About 10 minutes. |

|

The Coolscan isn't the only scanner with the Digital ICE features, and there are enthusiastic users of other brands who will swear by them. Sadly, Nikon no longer makes these wonderful scanners, but they can be found on eBay, and several hobbyists have the ability to clean and refurbish them. There are also other scanners you can get new, but unfortunately none match up with the Nikons. Whatever scanner you get, if it doesn't have the Digital ICE feature (or something comparable under a different name - look for "Infrared cleaning") don't get it.

As good as the Coolscan is, it's not perfect. Here are a few things to consider:

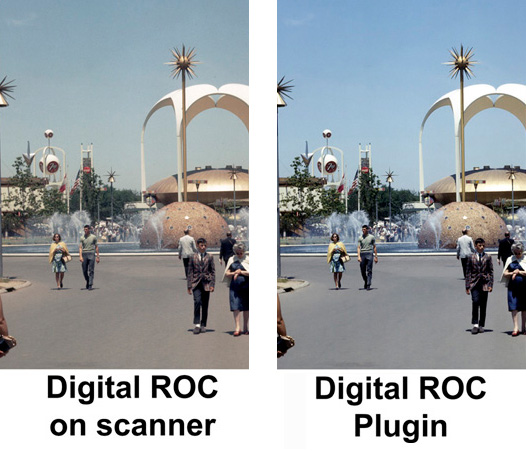

First, the Digital ROC (Recovery of Color) option built in to the scanner has a problem with fixing colors on Kodachrome slides. The emulsion on that type of slide confuses the processing algorithms and produces some unpredictable results. In that case you can scan with just the dirt and scratch removal feature turned on, then fix the colors in Photoshop or another image editing program. Kodak once sold some great tools for this as plug-ins to Photoshop and other programs, but have now discontinued them, and they are limited to 32-bit applications. There are other tools that can get close, and you can also do this adjusting manually.

Here's an example of how Kodachrome can confuse the scanner. The image on the left used the built-in ROC feature of the scanner, which resulted in a grayish and washed out image. The right one was scanned with Digital ICE turned on in the scanner to remove scratches and dirt but with ROC left off, then adjusted with the software plug-in for a more pleasing version. |

|

Another issue is that Digital ICE, the scratch and dirt removal tool in the scanner, doesn't work on most black-and-white negatives, so those scratches will have to be handled manually. There are some ways to minimize the work in your photo editing software, but be prepared for a lot more effort.

The Coolscan also has problems with pictures that have a lot of blue in them. A shot of a blue sky over a blue lake will often come out looking less than realistic, with many other sections taking on a distinct yellow hue, and/or being way too dark. In this case it can be usually fixed in the same manner as a Kodachrome slide.

The Coolscan is designed for 35mm images and cannot be used on larger format film. In some cases you can use it for smaller images, but instead I suggest a flatbed scanner. I use an Epson V700, which has Digital ICE built in. The Epson handles a wide range of film sizes and prints, and through the magic of Digital ICE does a very nice job indeed. It's much slower than the Coolscan, though, and the recovery tools are not as precise as on the Nikon, so I use it only for those jobs the Coolscan can't readily handle. Between all of these tools it's possible to get just about anything into the computer.

The following Pana-Vue slide from the 1964 Fair has too large an image area for the Coolscan so I used the Epson. The Epson has a color correction mode but I prefer the results from the Kodak software, so it was scanned without that feature turned on. |

|

It only took a few minutes of tweaking to get rid of the red. I'm still in awe of what the brains behind the scanner and the software have been able to revive from the dead. There sure wasn't any blue sky or green grass in the original version. |

|

2) Resolution and size

One question I get asked a lot is how high a resolution to use. I recommend going as high as you can, and later downsizing the image if you need a smaller size. For example, most web pages are at 72 DPI, but if you scan at that resolution you're likely to be quite disappointed. One thing to watch for - the stated "maximum resolution" of many scanners is misleading, as some will claim results gained through software interpolation. You want to look at the true optical resolution.

Here's an example of how a higher resolution produces a much better result:

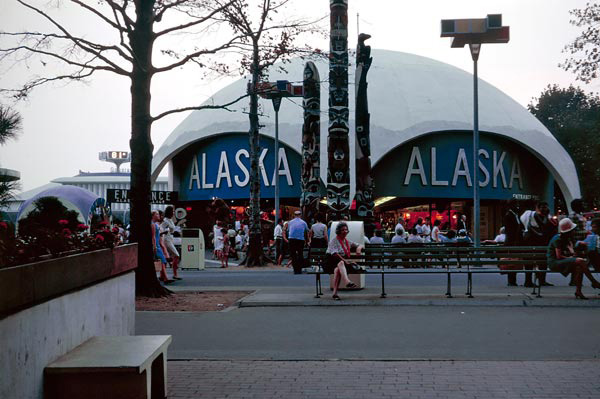

This picture of the Alaska Pavilion at the 1964 Fair was scanned at 2900 DPI on a Nikon Coolscan IV. |

|

Here's the same slide rescanned at 7200 DPI on a Plustek 7600i scanner. This version is obviously brighter but it's also a great deal sharper. I do most of my work on Coolscans but some darker slides come out better on the Plustek - but it is a far slower scanner and the dust removal is less powerful than the Coolscan. |

|

3) What about prints?

Most of my world's fair and theme park collection consists or slides or negatives, but I also have a number of prints that have seen better years. For these I generally use an Epson V700 flat-bed scanner. The V700 has Digital ICE, which is a definite plus, and also has a proprietary dust removal setting that sometimes works better. It also has a color correction option, but I generally forgo that and do the color work in Photoshop.

This print of the Cinema 360 pavilion at "Man and His World" in 1971 has faded significantly over the years. It was scanned with the Digital ICE feature on the Epson V700. That removed most of the dirt; what remains is a bit tough to see in this reduced size version but it's there! |

|

The photo cleaned up nicely, with some dirt removed automatically through a Photoshop filter, and the rest taken out manually. |

|

4) The next step is the editing software

I am a big fan of Adobe Photoshop, and use it for 99.9% of my editing. A friend of mine gets excellent results from Corel Paint Shop Pro. Whatever tool you pick, I suggest it be able to use Photoshop plug-ins, which allow you to greatly extend the capability of the editing program. Why do you need an editor if the scanner is so good? Well, as amazing as it is, some things are just beyond it.

This slide of the Montana Pavilion at the 1964 Fair went through the scanner with the correction features turned on, and the colors have been adjusted, but there's still a lot of dirt visible. |

|

Here's the reason why. All of this junk is printed on the slide, which is a commercial souvenir sold at the Fair. Poor quality control by the vendor has created a messy slide indeed. Since the dirt is printed on the slide it can't be detected through the infrared process. |

|

Manual editing with several tools in Photoshop have removed the junk and produced a sharper image. |

|

While the scanner will get rid of most of the dirt and scratches, there will be some defects that it won't be able to handle for you. In those cases you'll have to become familiar with Photoshop's "Healing Brush" and cloning features. Some of the automatic Photoshop features such as dust or scratch removal cause too much image degradation for my taste, so it's time then to start playing artist and fix things by hand.

This negative of "Riders of the Elements" at the 1939-1940 New York World's Fair has picked up more than a few scratches over the years. The Epson V700 was able to remove some of them with the infrared correction option, but enough remained to distract from the subject of the picture. |

|

It took a good amount of manual effort to get rid of the scratches, but when it was done the picture didn't look like it came from an 80+ year old negative. |

|

There are lots of other things you can fix on your old pictures. As the first example on this page shows, you can fix the lightness or darkness of areas, even if the original picture was over or under exposed - within reason, of course! Colors can be fine-tuned, sharpness adjusted, etc. Just because the original doesn't look good doesn't mean it should be tossed away.

This picture of an audience inside the New York State Pavilion at the 1964 Fair looks unsalvageable at first glance. At this stage the dirt and scratches have been dealt with but the picture is still a mess. |

|

Some tweaks in Photoshop and it looks better than when it was taken. |

|

It's not just over-exposed pictures that can be fixed. They're usually harder to save, but some very dark ones can be made good enough to keep. A tip: the higher a DMAX number a scanner has, the better the chance you can do something with dark images.

This picture of the sailing ship Columbia at Disneyland in 1965 obviously has some problems. Way under-exposed, it also has some dirt, and some mold, as seen in the upper right corner. |

|

Once again the combination of a Coolscan and Photoshop have worked wonders. |  |

There are lots of other things you can fix on your old pictures. Colors can be fine tuned, sharpness adjusted, etc. Just because the original doesn't look good doesn't mean it should be tossed away. The last version of Photoshop didn't do some of these things automatically; who knows what the next version might be able to do to one of those "bad" slides. Never toss them out.

5) Fix it in post production

I spent about 20 years working at different movie studios, and one common refrain heard any time something went wrong on the stage was "We'll fix it in post production." Those guys could do magic - and so can you.

What happens if you have a picture that you really like except for a power line in the way, a kid making a face at the camera or people standing in the way of your favorite pavilion?

It's a nice day at the New York State Pavilion, but every time you tried to take a picture someone got in the way. |

|

What people were those? Spend some time in Photoshop and send them on their way. |

|

Someone else is in the way, but he won't be for long. |

|

There are some amazing tools out there that can do much of this automatically, and you can then fine-tune the results. |

|

The Lunar Fountain at the 1964 Fair would look better if someone wasn't in the way, right? |

|

It took about 30 minutes to edit her out of the shot. You can get rid of random strangers, or perhaps unwanted ex-relatives! It's all just a question of how much time you want to spend on it. |

|

Ready to get going?

I hope this short introduction to "Fun with Photoshop" encourages you to dig your old pictures out and to bring them back to life. If I can answer any questions for you (short of a course in Photoshop 101) please let me know. If you're sitting on the fence and aren't sure if your pictures can be salvaged, drop me a line. I might be able to do one for you just to encourage you a bit further. I don't do wholesale restorations for others as a general rule (just no time available), but if you have something special in mind let me know.